In a landmark decision, a Hong Kong[1] court has for the first time ruled that cryptocurrency is “property” under Hong Kong law. In this Part 1 of our two-part series, we analyse the court’s decision, consider its key implications and discuss the judicial position on this issue in Mainland China.

1. Introduction

On 31 March 2023, in the landmark decision of Re Gatecoin Limited (In Liquidation) [2023] HKCFI 914 (“Gatecoin Case”), the Court of First Instance of Hong Kong has, for the first time, ruled that cryptocurrency is “property” under Hong Kong law.[2]

The Gatecoin Case is aligned with the Hong Kong Government’s policy statement that, in order to enhance investor protection, there is a possibility of introducing a statutory definition of cryptocurrency as property, while recognising that the unique characteristics of cryptocurrency may differ from traditional assets.[3]

In ruling that cryptocurrency is “property”, the Gatecoin Case brings Hong Kong’s jurisprudence in line with other major common law jurisdictions. Interestingly, despite Mainland Chinese regulators’ imposition of a general ban on cryptocurrency trading, the judicial position in Mainland China on the legal status of Bitcoin also broadly aligns with that in major common law jurisdictions.

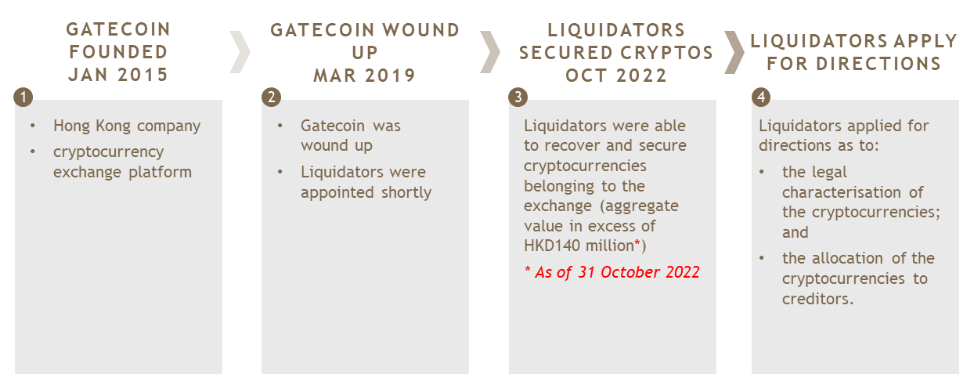

2. Background of the Gatecoin Case

Gatecoin Limited (“Gatecoin”) was a Hong Kong-incorporated company that operated a cryptocurrency exchange platform (“Gatecoin Exchange”) which traded over 45 types of cryptocurrencies. Gatecoin entered into insolvency proceedings in March 2019 and joint and several liquidators were appointed shortly thereafter. The liquidators managed to recover cryptocurrencies with a total value of approximately HK$140 million and, pursuant to Hong Kong’s insolvency legislation, subsequently sought directions from the Hong Kong Court on the following key issues:

- (Issue 1) Whether the cryptocurrencies were held on trust by Gatecoin for the benefit of its customers?

- (Issue 2) Whether cryptocurrency is “property”? This issue is important because pursuant to Hong Kong’s insolvency legislation, a liquidator has an obligation to take into custody all “property” of a company upon a winding up order in respect of that company.[4]

3. Cryptocurrency is “property” under Hong Kong law

3.1 Cryptocurrency satisfies the four-prong test for “property” established in the Ainsworth Case

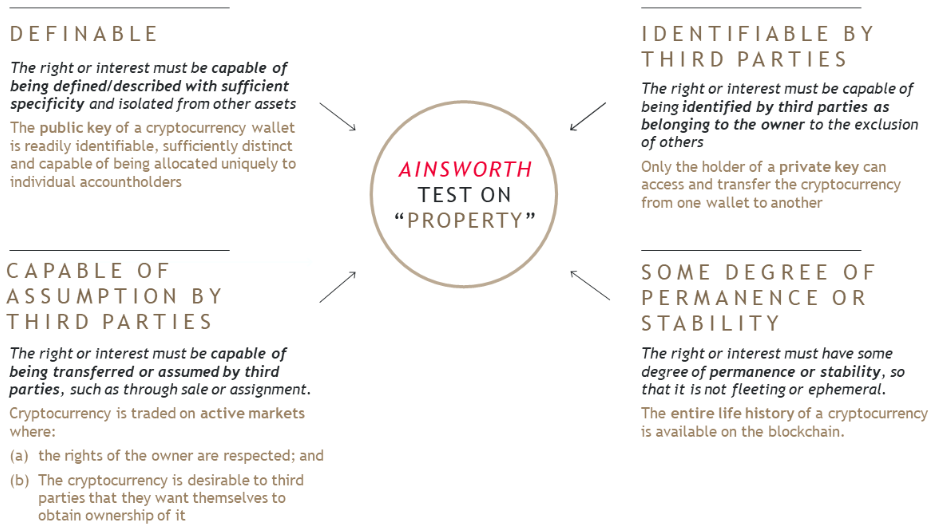

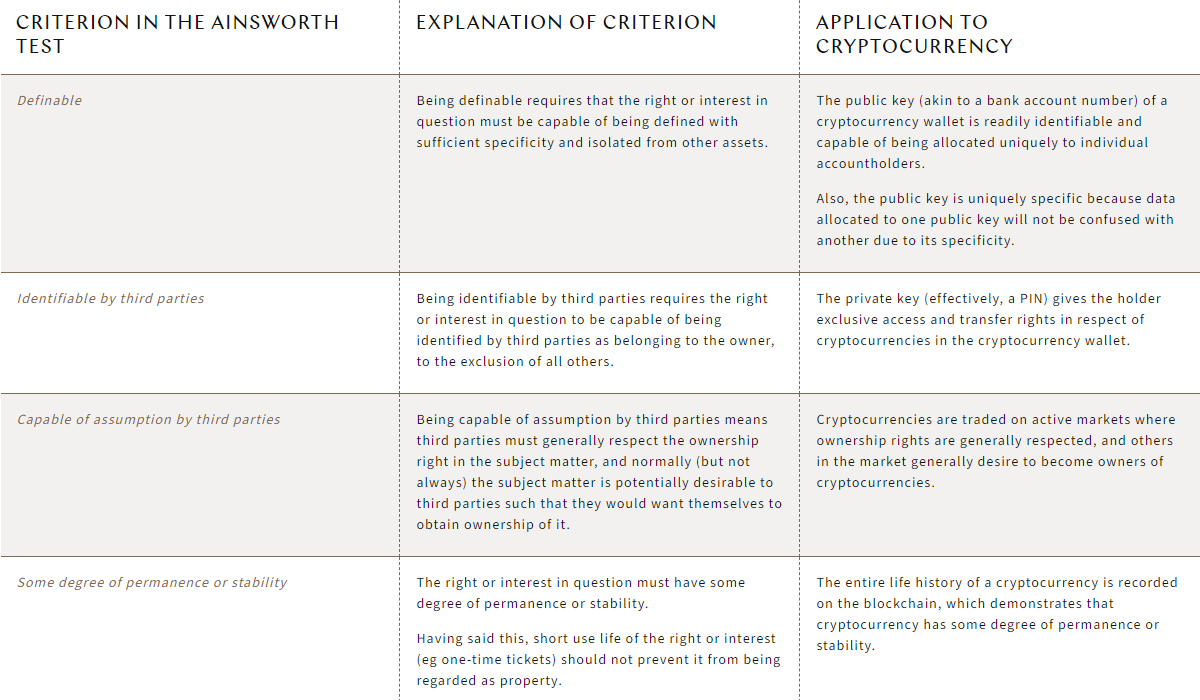

The Hong Kong’s insolvency legislation does not define the term “property”, although the Interpretation and General Clauses Ordinance contains a broad and inclusive definition of “property”.[5] The Hong Kong Court, like the courts in many other common law jurisdictions, applied the common law definition of “property” established in National Provincial Bank v Ainsworth [1965] AC 1175 (“Ainsworth Case”) to determine whether cryptocurrency constitutes property.

The Ainsworth Case sets out a four-prong test which provides that, in order for a subject matter to be “property”, it must be “[1] definable, [2] identifiable by third parties, [3] capable in its nature of assumption by third parties, and [4] have some degree of permanence or stability”.[6]

With reference to the unique characteristics of cryptocurrency, including the public key (which is analogous to a bank account number) and the private key (which is analogous to a PIN or password), the Hong Kong Court in the Gatecoin Case concluded that cryptocurrency had all the attributes of “property”.

We examine each element of the four-prong test set out in the Ainsworth Case and its application in the Gatecoin Case below.

Having considered the four-prong test in the Ainsworth Case, the Hong Kong Court in the Gatecoin Case noted that the definition of “property” in Hong Kong is an inclusive one and is intended to have a wide meaning. Accordingly, the Hong Kong Court decided to follow the reasoning and conclusions in:

- the New Zealand High Court decision of Ruscoe v Cryptopia [2020] NZHC 728 (“Cryptopia Case”) (which the Hong Kong Court described as the most detailed analysis on the issue of whether cryptocurrency is “property”); and

- the UK Jurisdictional Taskforce’s Legal Statement on Cryptoassets and Smart Contracts (“Legal Statement”).

Both the Cryptopia Case and the Legal Statement[7] concluded that cryptocurrency is property under the common law definition.[8]

3.2 Implications of cryptocurrency being recognised as property

There are a number of important legal consequences flowing from the decision in the Gatecoin Case that cryptocurrency is property under Hong Kong law. For example:

- the Gatecoin Case creates legal certainty and brings Hong Kong’s jurisprudence in line with other major common law jurisdictions (including England and Wales, the British Virgin Islands, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States) in classifying cryptocurrency as “property”.

We also observe that courts in some common law jurisdictions only considered whether a specific type of cryptocurrency (eg Bitcoin or Ether) falls within the definition of “property” (or its equivalent term). In this respect, the Gatecoin Case is significant because the Hong Kong Court

- Cryptocurrency is capable of being the subject matter of a trust – enabling the separation of legal and equitable interests, which is important for a variety of commercial and financing transactions.

- It is legally possible to create a security interest over cryptocurrency as collateral.

- It is now clear that liquidators must take cryptocurrency into custody as “property” upon a winding-up order under Hong Kong’s insolvency legislation.

4. Judicial pragmatism – an alignment of judicial positions in Hong Kong and Mainland China

4.1 Judicial pragmatism in the Gatecoin Case

Notwithstanding the novelty of the technology underlying cryptocurrency, the analysis on its legal characterisation in the Gatecoin Case still involved applying well-established common law principles (such as the four-prong test in the Ainsworth Case). This is a good demonstration of the flexibility and judicial pragmaticism inherent in the common law system.

4.2 Judicial pragmatism in Mainland China

We observe that similar judicial pragmatism also applies in the context of the considerations of the legal nature of cryptocurrencies in Mainland China.

For example, in May 2022, in a case on the legal nature of Bitcoin and its owner’s right to compensation (“Shanghai Bitcoin Case”), the Shanghai High People’s Court ruled that Bitcoin is a “virtual asset”, subject to the property law. In its decision, the Shanghai Court:

- considered the ongoing debate in Chinese academic circles about the legal characterisation of Bitcoin and observed that existing academic theories only focussed on certain aspects of Bitcoin to support their respective propositions and were not comprehensive. For example, the Shanghai Court was not persuaded by the theory that Bitcoin is a type of intellectual property because the Bitcoin mining process does not involve human intellectual creation or input. The Shanghai Court also disagreed decentralised Bitcoins should be classified as a form of debt;

- stated that classifying Bitcoin as a unique and new form of property faces hurdles in civil law jurisdictions (such as Mainland China) because of the “numerus clausus principle”, which requires there to be a statutory or legal basis for the types and features of property rights under Mainland Chinese law and provides that new forms of property rights cannot merely be created by private contract; and

- applied the principle of judicial pragmatism (in Chinese: 司法实用主义) and stated that the Court would extend property law principles to protect Bitcoin, but without directly commenting on the legal characterisation of Bitcoin. In applying the principal of judicial pragmatism, the Shanghai Court not only cited other Mainland Chinese court decisions, it also referred to the 2013 Notice on Preventing Risks Associated with Bitcoin issued by five Mainland Chinese governmental bodies including the People’s Bank of China (“PBOC”), which described Bitcoin as a virtual commodity.[9]

In its decision, the Shanghai Court recognised that: (a) Bitcoin clearly has economic value and confers economic benefits; (b) the total number of Bitcoin is finite; and (c) Bitcoin holders can possess, use and dispose of Bitcoin. Therefore, the Shanghai Court concluded Bitcoin has economic value and all the hallmarks of property, and should be protected by applicable property law under the principle of “judicial pragmatism”.

Although Article 127 of the Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China provides for the protection of virtual property, it does not define such concept or specify its application. The reasoning in the Shanghai Bitcoin Case sheds light on the connection between modern judicial practice and legislation in Mainland China, and to some extent stands for the propositions that Mainland Chinese courts:

- are willing to be “practical” and apply “judicial pragmatism” to reach a common sense result; and

- attach significant weight to Mainland Chinese regulators’ views and policies, even if such views and policies are conveyed in a “notice”, which is not technically a statute or regulation.

4.3 Supreme People’s Court’s position on cryptocurrency

The Supreme People’s Court has expressed its views on the legal characterisation of cryptocurrency in the recently published consultation draft of the Minutes of the National Courts’ Financial Trial Work Conference (in Chinese: 全国法院金融审判工作会议纪要(征求意见稿)) (“Draft Conference Minutes”). The Draft Conference Minutes include extensive discussion of how Mainland Chinese courts should judicate financial cases involving cryptocurrency.

Certain contracts involving cryptocurrency may be valid

The Draft Conference Minutes begin by stating that trading and speculative activities involving cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin and Ether have seriously disrupted the economic and financial order as well as the rights and interests of members of the public. The Draft Conference Minutes note that in order to prevent speculation over cryptocurrencies, the Mainland Chinese regulator has issued a number of policies and measures clarifying that cryptocurrencies are not legal tender and imposing a general prohibition on cryptocurrency-related activities.

Notwithstanding the general ban on cryptocurrency related activities, the Draft Conference Minutes state that cryptocurrency has the attribute of virtual property. This aspect of the Draft Conference Minutes is broadly consistent with the Shanghai Bitcoin Case. The Draft Conference Minutes further state that where the parties agree to using a small amount of cryptocurrency as compensation for contracts such as labour contracts, the Mainland Chinese courts should uphold the contracts as valid, provided that there are no other grounds for contractual invalidity. If one party requests the other party to perform its obligation to deliver cryptocurrency, the Mainland Chinese courts may support such obligation, but if such obligation cannot be performed due to policy restrictions on cryptocurrency-related activities, the non-performing party shall compensate the other party by paying an amount equal to the actual value of the cryptocurrency in question.

Validity of contracts involving cryptocurrency that performs a similar function to fiat currency would be quite doubtful

Notwithstanding the foregoing, the Draft Conference Minutes note that where a party uses cryptocurrency as a regular payment tool to exchange for fiat currency or pay for goods under the guise of an underlying transactional contract, the Mainland Chinese courts should find the contract to be invalid. In other words, as a matter of Mainland Chinese law, the validity of a contract under which a cryptocurrency performs a similar function to fiat currency would be quite doubtful. The same view is confirmed in the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the People’s Bank of China (Draft for Comments)[10] (in Chinese: 中华人民共和国中国人民银行法(修订草案征求意见稿)) (“PBOC Law Draft Amendments”), which clarifies that no entity shall produce or sell cryptocurrency to replace the circulation of RMB in the market.

5. The future of cryptocurrency in Mainland China?

As noted in the Draft Conference Minutes, there remains a general ban on cryptocurrency-related activities in Mainland China. For example, in September 2021, the PBOC together with nine other Mainland Chinese ministries, commissions and judicial bodies, jointly issued the Notice on Further Preventing and Resolving the Risks of Virtual Currency Trading and Speculation (“2021 PBOC Notice”)[11], which states that business activities related to cryptocurrencies are illegal financial activities and services provided by an overseas cryptocurrency exchange to Mainland Chinese residents via the Internet are also illegal financial activities. Specifically, the 2021 PBOC Notice provides that:

“Exchanging legal tender for virtual currencies or vice versa, exchanging one virtual currency for another, buying and selling virtual currencies as a central counterparty, providing information and pricing services for the trading of virtual currencies, issuing tokens to raise funds, trading virtual currency derivatives, and engaging in other virtual currency-related activities are potentially instances of illegal issuance of coupons as substitutes for the legal tender, unauthorized public offering of securities, illegal conduct of futures business, or illegal fundraising. Such activities are unlawful and strictly prohibited by law, and shall be forcibly banned in accordance with the law. Any person that has committed such illegal financial activities that constitute a crime will be prosecuted for criminal liabilities […]. Provision of services by overseas virtual currency exchanges to residents in China via the internet is also considered to be an illegal financial activity.”

Despite the general ban on cryptocurrency-related activities described in the 2021 PBOC Notice, new digital technologies adopted in some cryptocurrencies, such as digital certificates, Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT), blockchain technology, etc, can still provide a valuable reference for the improvement and development of the financial system.

Also, the 2013 Notice on Preventing Risks Associated with Bitcoin clearly states that “in nature, Bitcoin should be categorised as a specific virtual commodity” (in Chinese: “从性质上看,比特币应当是一种特定的虚拟商品”). This officially recognises that cryptocurrency has the legal nature of virtual property, and subsequent judicial decisions and the Draft Conference Minutes also recognised the same position, showing the consistency and continuity of the regulatory policies on cryptocurrency of the Chinese Mainland Government.

We closely follow crypto-related legal and regulatory developments in Mainland China and would be pleased to share our insights with you.

6. Where can I learn more about the Gatecoin Case, the Shanghai Bitcoin Case, the Draft Conference Minutes, and their impact on my business?

The cross-border financial regulatory and structured finance team at KWM has extensive experience advising international and PRC-based financial institutions and fintech companies on a broad range of cryptocurrency, blockchain and NFT-related matters.

Our team of fully bilingual partners and lawyers are familiar with applicable cryptocurrency-related laws and regulations in Hong Kong and Mainland China. We also regularly advise established financial institutions as well as emerging fintech companies on licensing, compliance and legal documentation issues relating to cryptocurrencies, cryptoassets and related derivatives products in Hong Kong and Mainland China. We are familiar with the unique and nuanced commercial and legal issues faced by Mainland Chinese companies and their counterparties in China’s fast-evolving crypto and fintech landscape.

[ad_2]